Episode 19: Whitney Houston (Whitney Houston, 1985)

“Background singers: Ask for them by name.” The joke, attributed to David Letterman points to the fact that backup singers are functional, serving at the pleasure of the lead voice, almost by definition, nameless. So it’s not every day that back-up singers make their way upstage those “twenty feet” and become household names.

One notable exception is Whitney Houston, whose singing career began backing up artists like Chaka Khan—you can hear her on the 1978 mega-hit, “I’m Every Woman”—and Jermaine Jackson and Lou Rawls.

It was Clive Davis, who first saw her perform in 1983, who championed her and drove her solo career as a musician to its initial heights. At Columbia Records, Davis built a stellar record in the 1960s and 1970s, helping to sign, among others, Bruce Springsteen, Janis Joplin, Billy Joel, Earth, Wind, & Fire, and Aerosmith. As the story goes, he was fired from CBS Records when he hosted his son’s Bar Mitzvah on the company dime, but he bounced back, taking business—and any future Bar Mitzvah funding responsibility—into his own hands, founding Arista Records, and signing a slew of great artists, including Barry Manilow (an early cash cow for Arista), Aretha Franklin (who happens to be Whitney Houston’s godmother) and Dionne Warwick (who happens to be her cousin).

It took two years to make Whitney Houston, her formally self-titled introductory record—her follow-up, in 1987, titled the foreshortened and colloquial, Whitney, signaled her ubiquity and popularity. She and the public were on a first-name basis now. Davis spared no expense on Whitney Houston, with Arista eventually spending over $400,000 against a $200,000 budget, which, at the time, was a lot for an unknown artist. And just imagine the Bar Mitzvah bash you could host with that kinda money.

Houston was blessed with an incredibly powerful voice and a humble demeanor, both honed growing up in the church. At the time of Whitney Houston’s release, she was 21 years, and many of the songs of the album embraced and accentuated her youth—especially in the power-pop “How Will I Know,” with its childlike “If he loves me, if he loves me not” breakdown and its questioning of a mother-figure who "knows about these things" (and here it might be interesting to note that Whitney's actual mother-figure, her mother, Cissy, was singing backup on the track) as well as the head-bobbingly popping “Someone For Me,” which explicitly places Houston in the role of shy teenage girl getting her love-legs underneath her. This squeaky-clean “boy of my dreams” lyrical content and puffy production, however, isn’t able to pull her off her mature and polished delivery. Houston had pipes.

It wasn’t all bubble-gum and trapper-keepers, though. Songs like “Saving All My Love For You” and “Greatest Love of All,” both of which became huge hits, delved into more adult themes of love and self-love. Funnily, in a July 1985 Ann Landers advice column, responding to a letter from a self-described “Eastern Liberal Square in Delaware” who is just terrified that the lyrics of her children’s music "encourage violence, promotes sexual promiscuity, and is extremely provocative," Landers lists “You Give Good Love” as an example (along with seven others) of sexually provocative, “trashy songs.”

(A quick note for those quick to jump down Landers’ throat, she did go on to say that while she doesn’t particularly care for the titles (nor the lyrics within the songs she may or may not have heard), there’s nothing really to be done. “Delaware,” in essence, should slow her roll. “Parents are always appalled at the music their teens listen to, but somehow the majority of teens manage to grow up OK, and some of them even become ‘Eastern liberals.’” Sick burn, Landers.)

While the lyrics of “You Give Good Love” are hardly sexually explicit, the music video for is, I admit, most definitely suggestive, or at least ham-handedly aiming for suggestiveness in the way that '80s music videos seemed somehow to perfect. Shall we dive in and give “You Give Good Love” a good hard look?

The video’s dramatic narrative follows an unexplained videographer in a patronless—I want to say… restaurant? after closing? as he gazes—both through the camera lens and (suggestively!) with his peeking, naughtily open eye around it—at the singer in the venue, played by Houston, who is outfitted (suggestively!) in a belted hot-pink unitard and backed-up by two spookily-lit backing singers. The very first sequence involves a tight close-up of Mr Videographer slowly—dare I say, suggestively—pushing his lens into the camera’s opening. Around a minute-thirty in, the cameraman’s head slowly tilts from his shouldered equipment so that both of his eyes can smile at her, and then the camera—our camera—cuts to an extreme and oh-so-suggestive close-up of the singer’s hands gently caressing the mic stand. Shots like these ping pong back and forth throughout: eyes, lips, hands, eyes, smile, lips. It’s hard to tell at this point if it’s just the very '80s-ness of the whole production that makes me see these moves as so comically ridiculous. But just wait, the suggestiveness takes a back seat to true ridiculousness once the kitchen staff gets involved.

Unable to cook at a time like this, the chef—creepily barechested beneath his open white coat, and glistening with sweat—comes out, removes his hat out of reverence, and gazes. Then his creepy sous-chef joins him, and they both leer and smile and disgustingly dip their fingers into the gruel the sous-chef was preparing—presumably for no customers—and, you know, suggestively taste it. (Blech.)

At three and a half minutes in, a third member of the kitchen staff has joined his colleagues and the sexual aggression has turned into a pitiful display of side-to-side dancing to the beat. It was at this moment that I remembered another music video of that time to feature not only a surfeit of aggressive sexual objectification within a restaurant, but an awkwardly dancing and wholly unsanitary kitchen staff. It was 1983’s “Hi, How Ya Doin’” by Kenny G on—what else?—Clive Davis’s Arista Records. That track, off his second record, G Force, which was more or less the general public’s introduction to Kenny G with its chart-reaching success, was produced by the now-legendary synthesizer guru and producer, Kashif. Any guesses on who produced Houston’s “You Give Good Love” a few years later? Mm hm. May the circle be unbroken. You all get an A. Class dismissed.

Modulations are sprinkled throughout the songs on the record—modulations being the shifting from one key center to another within the same song, usually producing a marked-if-mild euphoria of refreshed arrival, not back home per se, but back home after Extreme Makeover: Home Edition completes its work—the same but different. One might even say that Houston’s genre-jumps on Whitney Houston show off the same character-inhabiting talents she displayed in her teenage career as a fashion model.

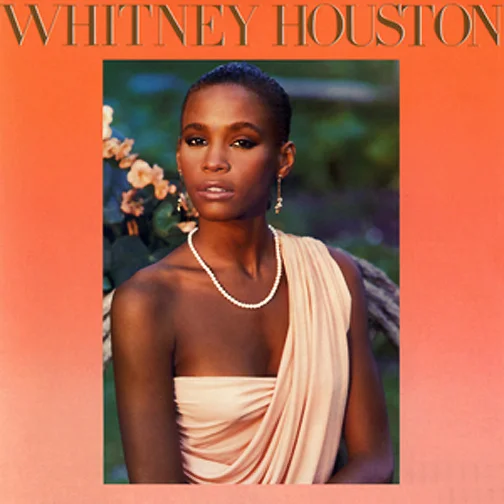

Indeed, the vocal range revealed in the songs—the quiet-fire R&B “You Give Good Love,” the jazz-tinted “Saving All My Love For You,” the pop-tarty “How Will I Know,” the broad, nearly-Broadway “Hold Me”—is mirrored in the wildly varied cover art photography across the singles: “You Give Good Love,” borrowing the regal, earthtone-infused album cover proper; “Thinking About You,” a tightly cropped black-and-white headshot set against a cold and angular geometric background; “How Will I Know,” which is chockablock with 80s teen fashion and graphic design; and the pair of “All At Once” and “Saving All My Love For You,” both featuring Houston draped in black, straight-faced and strong-as-hell as she wades in the ocean with—you guessed it—a horse. I’ve always said, If you’re gonna spend a chunk of your $400,000 album budget on a day at the beach with a horse, you might as well squeeze two covers out of the shoot. But in all seriousness, what comes through in all of the cover photos and, importantly, in all of the songs, is her dignity, intact—see the song “Greatest Love of All” for details—no small feat for a young woman being groomed by a label to take the world by storm.

Taken as a whole, Whitney Houston (the record) does a great job of marking a moment in time—pulling as it does into one album stylistic elements that were taking hold in the early 80s—but also marking the arrival of Whitney Houston (the artist) onto the world stage, implicitly stating, “You will remember my name.”

And we did.

I’m Josh Rutner, and that’s your album of the week.