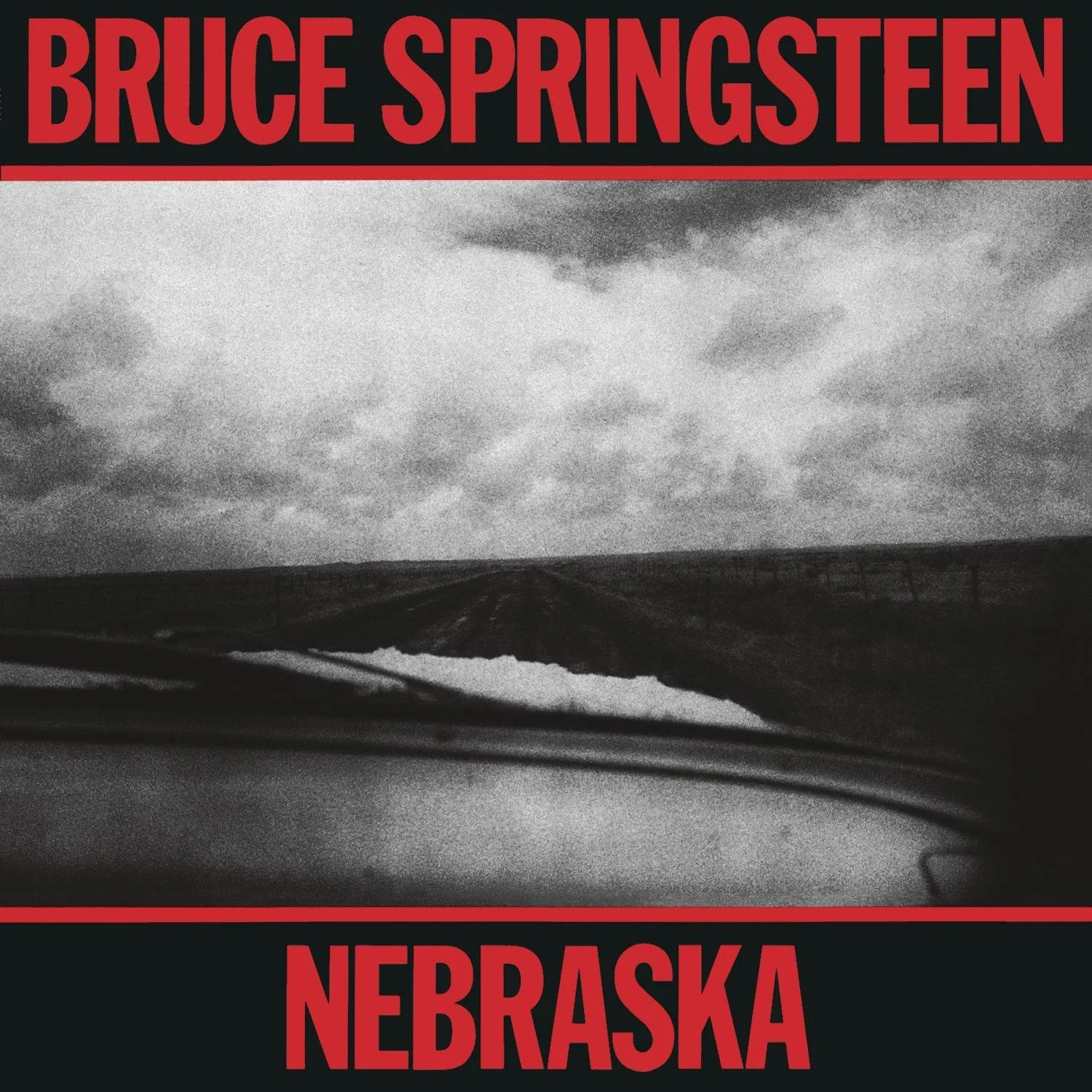

Episode 27: Nebraska (Bruce Springsteen, 1982)

Taste and judgement: the two needn’t align. In fact, as W. H. Auden once wrote, “As readers, we remain in the nursery stage so long as we cannot distinguish between taste and judgment, so long, that is, as the only possible verdicts we can pass on a book are two: this I like; this I don't like.” He went on to list the five possible verdicts that an adult reader (so to speak) might come to. Four of them seem obvious enough:

- I can see this is good and I like it;

- I can see this is good but I don't like it;

- I can see that this is trash but I like it; and

- I can see that this is trash and I don't like it.

But it’s the fifth verdict—the one Auden drops without fanfare between the pair of pairs above—that I view as the most compelling, and, given that in this episode we’ll be discussing Bruce Springsteen—that hugely popular icon that divides listeners into believers and non-believers—the most apt: “I can see this is good and though at present I don't like it, I believe that with perseverance I shall come to like it.”

For as long as I can remember, The Boss has been for me back-burner at best. More often than not, I wrote him off as a wheezing phony, whose pedestrian, workaday lyrics—masquerading as high art—were laid atop unimaginative and uninspired bedding, supplied by what sounded to me like a solid corporate wedding band. And yet! I’ve never given up the idea that with perseverance I might find a way in, if not actually come to like it.

In 2011, I attended a birthday concert for Sting at the Beacon Theater in New York, and among the long list of musical guests, which included Stevie Wonder, Billy Joel, Lady Gaga, Mary J. Blige, Vince Gill, and Herbie Hancock, was one Bruce Springsteen. When he appeared on the stage toward the end of the show, alone with a twelve string—fans in the audience performing their traditional “Bruuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuce” welcome—I braced myself. What I heard in that solo, out of time version of Sting’s “Fields of Gold,” was shimmering and lovely, sensitive and solid, humble and confident. The door had creaked open a crack, and I glimpsed the golden light. There was a way in for me.

He followed up with a full-band reading of another—admittedly, Springsteenian in tone—Sting tune, “I Hung My Head,” which tells of a man who accidentally shoots another, and the utter existential shame it brings upon him. Springsteen takes the liberty—as Johnny Cash had before him, in his 2002 cover—of pulling the tune down out of its original liltingly crooked 9/8 time signature, into the four-beats-per-measure signature of the every man. In hindsight, the odd-meter treatment of the original almost feels more clever than anything else.

Springsteen sold me that night, providing me at very least a foothold that I might use to find the next.

A few weeks back, I asked my most knowledgable and Springsteen-minded friend which album he thought I should cover. And in an instant, he said, “Nebraska.”

The 1982 record, Springsteen’s sixth, has a good deal going for it for someone like me. Fittingly, while it’s not necessarily the top choice for John Q. Brucehead, it’s been referred to as “the only record you can push on the non-believers.” Among other things, it’s a one-man, bedroom production: no E-Street Band, nor throngs of screaming die-hards to contend with.

Rather than spend the cash working out demos in the studio, he had asked his guitar tech, Mike Batlan, to get him set-up with one of those newfangled portable four-track cassette recorders in his Colt’s Neck, NJ house. The songs he produced there in early January, 1982—layered with guitar and mandolin; glockenspiel and harmonica; organ, synth and tambourine—were intended to act as demos to give his band an idea of what he was aiming for. The four-track recordings were mixed down through a guitar Gibson Echoplex unit, and then onto a boom box. “Not finely-honed recording equipment,” Springsteen would laughingly admit, but the kind of boom box you take to the beach that “sucks in the sand and keeps playing.” This questionable equipment helped lend Nebraska its patina. And when the band couldn’t successfully recapture its eery aura in the studio, the demo cassette, which Springsteen had been carrying around willy-nilly in his pocket for three weeks, was—aside from some serious mastering to clean up all the tape hiss—released as it was.

Do I like this album? I do.

In the spirit of affirmation, let me count the ways:

- I like the vulnerability—in his vibrato on “Mansion on the Hill,” in his glockenspiel playing on “Used Cars,” in his awkward-but-earnest squeezing of the lyrics “’Til the sign said ‘Canadian border 5 miles from here’” in the end of a phrase in “Highway Patrolman.”

- I like that he packs his bleak lyrical themes in major keys, the way Kelly Joe Phelps talks about hiding his dark stuff in the waltzes.

- I like that he indulges in the true-crime story of the spree killer Charles Starkweather as fodder for a song, continuing the dying tradition of the murder ballad.

- I like that his harmonica is so hot in the mix—at times enough to make you wince—just as Bob Dylan’s was at the end of his “Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right.”

- I like Springsteen’s prairie-ish background yelps, barks, and hollers, and I especially like the completely wild-eyed, hazy-minded, delay-drenched, full-throatedly paranoid scream at the end of “State Trooper.”

- I like that that same paranoid narrator in “State Trooper” has “done things” but we aren’t let in on what they are.

- I like the description of bleak and cold desperation that can lead a man toward sin in “Johnny 99.”

- I like that the closer, “Reason to Believe,” sums up the mind-boggling and unexplainable perseverance of those faced with seemingly dead ends.

If nothing else, I can now say that there’s a Bruce Springsteen record that I truly like. And Nebraska, a deeply personal album that strips away all those excesses I’d come to see as bound up with the artist and his music, has given me reason to believe that, while I do acknowledge the goodness of much of Springsteen’s catalog, with perseverance, I shall come to like more and more.

I’m Josh Rutner, and that’s your album of the week.