Episode 9: Love is Overtaking Me (Arthur Russell, 2008)

In May of this year, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts announced it had acquired the archives of Arthur Russell, that shy but insistent and ever-prolific composer-singer-cellist-producer who helped shape the New York downtown scene in the 1970s, in part through his work as the Musical Director of The Kitchen, pulling together into one venue so-called minimalist music, New Wave, folk, and avant garde multi-media performances—along with more unclassifiable things.

Russell himself was a musical polyglot, contributing discretely—and, often, discreetly—to, among others, the avant-garde, new wave, and disco scenes. The Russell archives include, according to the NYTimes’ Ben Ratliff, “a thousand-or-so reels, cassettes, DATs, Beta, and VHS tapes with hundreds of hours of unreleased and probably unreleasable material, representing how Russell made his work.” Such an archive, made public, is a huge boon for fans of Russell, who was process-obsessed and always on the hunt for new sounds. There will be much to wade through.

Since 2004, the record label called Audika Records has been working with Tom Lee, Russell’s long-time partner and the executor of his estate, to lovingly pore over those hundreds of hours of material to curate compilation albums that help bring to light the breadth of Russell’s work. Unlike Franz Kafka or Virgil, who coyly requested of others that their manuscripts be burned upon their death—and, the fact that they didn’t just quietly toss them into a fire themselves speaks to the reluctant wink that might’ve accompanied such requests—Russell did no such thing, reveling as he did in the open and and the unfinished form. In fact, according to Lee, much of the material left behind consists of songs that Russell wanted to release, “but nobody would put ‘em out.”

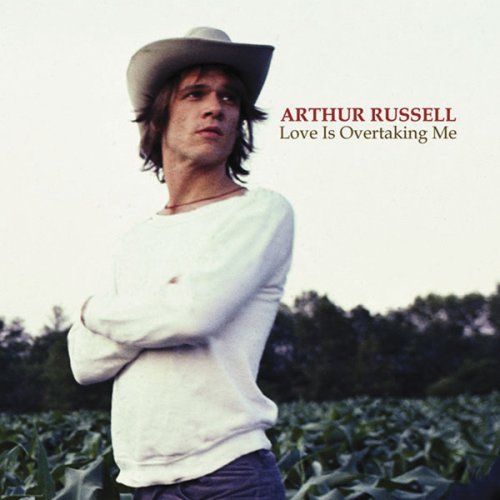

This week we focus on the 2008 Audika compilation called Love is Overtaking Me, a bringing-together of some of Russell’s more straight-forward song forms recorded in the long stretch between 1974 and 1990, up to two years before his death. It’s a twenty-one-track journey through homemade demos and fully-produced, full-band studio efforts. The stetson that the Iowa-native wears on the cover photograph—arms crossed, three-quarter profile in front of a field—foreshadows the touch of country that seeps into and out of some tunes. The most obvious is the cowboy-campfire waltz that opens the album, “Close My Eyes.” The song that follows, an actual, traditional cowboy song, “Goodbye Old Paint”—Old Paint being the name of a horse—might very well have been too on the nose, but Russell’s arrangement throws one for a proper loop with its Indian tambura drone and trotting tabla, and its clarinet, flute, and strings leaning heavier on raga than lasso.

The accessibility of the grooves and genre-work on this collection has been given the hairy eyeball by some critics who privilege Russell’s more “penetrating and demanding” work, but the privileging itself is antithetical to Russell's flat-and-wide, horizontally-interconnected underground networks approach. Indeed, if anything, it would be accessibility that was to be privileged in Russell’s work. He aimed to liquefy raw material to where concert music and popular song can criss cross. “In bubble-gum music the notion of pure sound is not a philosophy but rather a reality,” he said in a 1977 interview. “In this respect, bubble-gum preceded the avant garde.”

The tenth track, “Eli,” a economical-and-sweet vignette about—on the surface at least—an underappreciated dog, is the only track on the compilation that foregrounds Russell’s cello. Unlike much of his cello-and-voice work, this brief song employs no echo effects. In the 2008 documentary Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell, we get to see and hear grainy footage of Russell performing “Eli,” alone with his cello in a modest venue on a wooden chair, drawing with his bowed double-stops the “ee” and “eye” vowel-sounds of the dog’s name as he sings it. It’s really something else.

A favorite of mine on the album is “Janine,” a moebius-strip of a form, half-twisted and eating its tail, in a small-scale way implementing his idea of creating musical structures that would allow listeners to “plug out and then plug back in again without losing anything essential.” The form cycles around and around but its asymmetry breathes life into each go-round.

Two years before writer Tim Lawrence published his biography of Russell entitled Hold On To Your Dreams, he published a really great monograph in the performance studies journal Liminalitites, called "Connecting with the Cosmic: Arthur Russell, Rhizomatic Musicianship, and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973–92." In it, he outlines concept of such rhizomatic musicianship, that is, musicianship that “moves repeatedly toward making lateral, non-hierarchical sounds and connections.” Lawrence quotes from Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s 1980 book, A Thousand Plateaus, which establishes a context for his rhizome riffing. “A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines,” they wrote. “The fabric of the rhizome is the conjunction ‘and… and… and…’”

With the wide-ranging Audika compilations already available and, soon—perhaps in a year, says the NYPL—the freshly-digitized audio from the Russell archives made available for online streaming, we have before us a beautiful opportunity to find our own paths through Russell’s “ever-anding,” and, to be inspired to “and” ourselves, again and again and again.

I’m Josh Rutner, and, that’s your album of the week.