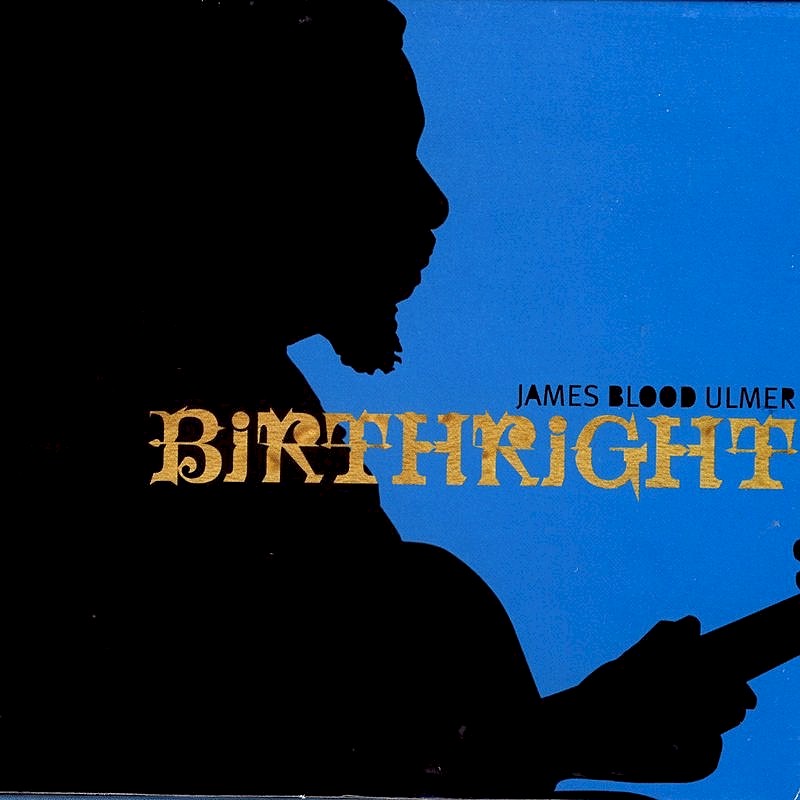

Episode 35: Birthright (James Blood Ulmer, 2005)

James Blood Ulmer’s 2005 solo release, Birthright, is an album best listened to alone in the dark, preferably at night. It is an exploratory pawing about in the world of the blues, using, to loosen the stone, the harmolodic tools forged by saxophonist Ornette Coleman, with whom Ulmer spent the majority of the 1970s studying and working.

While it seems after listening only natural that Ulmer would have recorded an album of blues, in fact his strict upbringing in rural St Matthews, South Carolina would draw a firm line between music for the church and blues music. Ulmer admitted to not knowing much about blues music before the guitarist and producer Vernon Reid suggested they collaborate on some projects that placed the devil’s music front and center, but of course the human element had long been in place: “A guy from the south ain’t got to play blues,” Ulmer would say, “because there’s blue shit all over that bad boy. You’re living the blues.”

Ulmer was reluctant, but Reid was insistent, helpfully pointing out the prevalent undercurrent of the blues beneath Ulmer’s beloved harmolodic so-called “free” jazz that he’d used for so long as his preferred mode of expression.

In a Down Beat interview published in 1983, Coleman defined harmolodics this way:

“Harmolodics is the use of the physical and mental of one’s own logic made into an expression of sound to bring about the musical sensation of unison executed by a single person or with a group. Harmony, melody, speed, rhythm, time, and phrases all have equal position in the results that come from the placing and spacing of ideas.”

It’s this freedom to play with harmonies, rhythms, phrase lengths, and so on, that ties harmolodics to the blues singers of the past. Playing by oneself helped to facilitate this freedom in a very real way—the twelve-bar blues is myth.

The lead-off track, “Take My Music Back to the Church,” is Ulmer’s way of facing head-on the stand-off between the church and the blues. He elevates the blues art form, sanctifies it, and claims that it is—or was, at least—misunderstood, singing: “Some people think it’s the song of the devil / but it’s the soul of the man for sure.”

He found a connection between the blues and church music not only in their respective ties to history, but in their single-mindedness toward a subject, which can lead you to a higher plane: “When you’re singing in church,” Ulmer says, “you’re not singing about nothing except God. So when you’re singing blues you can get a similar feeling—that you’re singing about something that’s not about you.”

From the start of “Take My Music Back to the Church,” we are washed-over by the open-fifth drone of Ulmer’s guitar—a favorite device of his uses to push his playing to new harmolodic heights while still feeling rooted “in key.” His novel open-tuning, consisting of four strings tuned to the same note complemented by a pair of structural fifths interleaved—a “harmolodic tuning,” in the words of a surprised Coleman upon first witnessing it—was literally dreamed up after being frustrated by Coleman’s drill-sergeant practice regimen where Ulmer would play chords for hours on end.

Sprinkled among the dark and deep and deeply original blues tunes on the record are a few bright and sparkling stunners, namely “Where Did All the Girls Come From,” which was originally released on his 1981 record called Free Lancing in full band format replete with back-up singers, and “Geechee Joe,” an oral history of sorts, telling the true story of his grandfather, a man who had grown up in the insolated Gullah/Geechee culture of the Sea Islands off South Carolina and Georgia. Joe had moved up to Pittsburgh, never working a job where he wasn’t the boss, for, as Ulmer’s song tells us, “he didn’t want to work for the white man.”

A favorite of mine is track five, “White Man’s Jail,” which is as close to a stereotypical blues form as we get on the record, but the lyrics—muffled and mumbled though they may be—combined with the patient and fluid strolling tempo, and Ulmer’s fluttering voice, make “White Man’s Jail” anything but pat. He takes one chorus of liberty to feature a guitar solo, but that’s it: one chorus. Talking of blues players who know what they’re doing, he says they “don’t take fifteen choruses, they play the song. If the song’s about a chicken, you don’t have the mule in there.”

After the album’s finale, a haunting and take-no-prisoners song called “Devil’s Got to Burn,” during which we hear Ulmer’s creepily devilish cackling, we are treated, after just over a minute of silence, to a coda in the form of a “hidden bonus track”—that vestige novelty that worked so well for CDs but sadly falls totally flat with the spoiler-filled scrubber bars of digital music interfaces—featuring a three-and-a-half-minute solo flute improvisation. It’s an unexpectedly light but welcome conclusion to a most-heavy record.

Do yourself a favor and wait until the sun goes down, turn off all the lights, put on Birthright, and turn it up.

I’m Josh Rutner, and that’s your album of the week.