Episode 42: Malvina Reynolds...Sings the Truth (Malvina Reynolds, 1967)

The first judge to be recalled and replaced in the state of Wisconsin was Archie Simonson of Dane County. It was 1977, but the circumstances surrounding his recall remain all too familiar today: faced with three teenaged boys who had pleaded no-contest to the gang rape of a girl in a high school stairwell, he added to the injustice of his paltry sentences the stunning insult of blaming the victim for dressing “inappropriately.” “Are we supposed to take an impressionable person 15 or 16 years of age,” he said of the teenaged rapists, “and punish that person severely because they react to it normally?” He went off on a tear and rattled off a handful more gems, complaining that he can’t go around exposing his genitals “like [women] can the mammary glands,” pointing out the existence of women in court rooms who have the gall to not wear a bra, and that women in court and in schools wear “dresses up over the cheeks of their butts.” Rolling Stone later quoted him as saying “Whether we like it or not, women are sex objects.”

Needless to say, the story made national news, and a petition to hold a recall election was successful, with over 36,000 signatures. One person in particular who took note was Malvina Reynolds, who, by 1977, nearing her 80s, was a well-established singer-songwriter. She took it upon herself to help the cause in the way she knew best: she wrote a song, called in favors to get it produced quickly as a single, and distributed them like handbills. The sleeve of the 45 had a two-paragraph detailing of the situation (with an all-caps headline, “THE JUDGE WHO SANCTIONED RAPE”) along with the lyrics of her freshly penned song, “The Judge Said.” If you’ll indulge me, these two verses of the song will give you a pretty good idea of the cut of her jib:

The judge said, Screw ’em!

Boys, you’re only human,

They brought it on themselves

By being born a woman.

Like a mountain’s there to climb

And food’s there to be eaten,

Woman’s there to rape

To be shoved around and beaten

Now if you beat a horse or dog

Or violate a bank,

Simonson will haul you in

And throw you in the clink.

But violate a woman,

Your equal and your peer,

The judge will slap you on the wrist

And lay the blame on her.

Simonson was recalled in that special election, and, in his stead, the people of Dane County voted in Moria Mackert Krueger, Madison’s first female judge.

Reynolds was a late-comer to the world of music. Born in 1900, she was approaching fifty when she first met Pete Seeger—nearly twenty years her junior—at a California hootenanny and hit him up for advice about how she might begin to do what he was doing. In Seeger’s words, “I remember thinking, ‘Gee, she’s kinda old to get started.’ I had a lot to learn. Pretty soon she was turning out song after song after song!”

Her voice was distinctively untrained. Contemporary reviews of her albums pointed out this fact with adjectives like “primitive,” “childlike,” “unsophisticated,” and just plain “not beautiful.” She herself acknowledged the lack of polish in her voice, but of course that was no matter. She saw her music as providing a function beyond the aesthetic: she wanted to effect real change. About the song “The Judge Said,” mentioned above, Reynolds would say, “We got out this great statement, this great song. And I say it’s great because it worked.”

Reynolds, above all, was interested in singing the truth. In her song, “What’s Going On Down There,” which appears on her second release, 1967’s fittingly titled Malvina Reynolds…Sings the Truth—this week’s Album of the Week—she speaks to the American political and legal system that looks to hold tightly to its power with white-knuckled fists against any sense of justice. The fix is in, she claims, with lyrics like: “They throw you in a jail / all covered with blood. / The higher-up man / won’t do you any good. / He also wears the hood.” Her airy, low-larynx’d notes—one of my favorite aspects of her voice—which appear here and there throughout this record, in this song act as a nice bit of text painting when she sings “down there.” The final verse issues marching orders to the listener: “We sing you this song / so you know what’s true / and you’ve gotta take it with you everywhere you go / because it’s up to you.”

The truth ain’t always easy to hear and Reynolds wasn’t known for being a softie. She is, after all, a singer of songs of discontent. In the thirteen songs on Sings the Truth, there are blatant or subtle references to slavery, nuclear testing, income inequality, racism, the KKK, middle-class conformism, and oh so much more. That said, sometimes even her toughest tunes are tempered with witty, gentle imagery and some are even downright funny.

The lead-off track, for example, “The New Restaurant,” is an acerbic mocking of the misplaced standards of modern era, by way of a comparison to a brand new restaurant, where all the superficial aspects—from gleaming fixtures and delightful crockery to masterfully laid-out menus and linen napkins and mats—are impeccable, but the food is terrible. The final verse contains the stinger: that in another generation—that’s us—the clientele would altogether forget the taste of food; that so long as waitresses are charming and the décor is “symphonic,” the people will happily eat plastic. There’s a video of Reynolds performing the song on Seeger’s short-lived, mid-’60s television series called Rainbow Quest, and at its conclusion we see a shot of her in profile, breaking character and shooting Seeger a smile-eyed, toothy grin, after which Seeger lays down his guitar and lets out an “Oh, that’s too sad!”

Reynolds was born Malvina Midler in San Francisco to immigrant parents who had joined the socialist party shortly after Reynolds’ birth. In later interviews, she referred to herself in her school years as “quiet, shy me.” That aspect of her personality is brilliantly laid bare in the hilarious song, “Quiet.” “I don’t know much about much,” she sings, “And what I don’t know I don’t say / And when I have nothing to say / I’m quiet.” But she was also a vocal activist at heart, leading protests and petitions even in high school. Note that the chorus of “Quiet” begins with the line, “When there’s occasion to holler, I’ll buy it / I can make noise with the best.”

Due to her parents’ opposition to U.S. involvement in World War I, her high school refused her her diploma. Nonetheless, she eventually found a way to enroll in UC Berkeley, and to receive, as she put it, “all the degrees possible,” culminating in a PhD in English in 1939. She graduated with honors straight into the tail end of the depression, and that, combined with the fact that she was slightly older than her classmates, a woman, and a Jew, contributed to her difficulty in landing a teaching job. She thus found herself tossed back in the thick of the working class movement, a movement whose message at the time she viewed as not being particularly well expressed for its intended audience to hear. Her work as a singer-songwriter would be her effort to smooth that seam between the radical movement and the People with a capital p.

If anyone is familiar with Reynolds’ work these days, it’s likely by way of her 1962 song “Little Boxes,” which was used as the theme song for the popular Showtime show Weeds. The song was written quickly, in a moving car while driving by the hills of Daly City, California on the way to a gig. If the OED is to be believed, the song stands as the earliest usage of the term “ticky-tacky,” a term meaning both the description of cheaply constructed buildings and the cheap or inferior construction material itself. It’s a great song, with a punch in its message that architectural mundanity and social mundanity go hand in hand: it’s not just the little houses that are made of ticky-tacky, but also the people who went to universities and came out all the same. They too are ticky-tacky. Seeger would cover the tune in 1963 and it resonated, even reaching number 70 on the Billboard Hot 100. Reynolds wouldn’t release her own version until Sings the Truth, four years later.

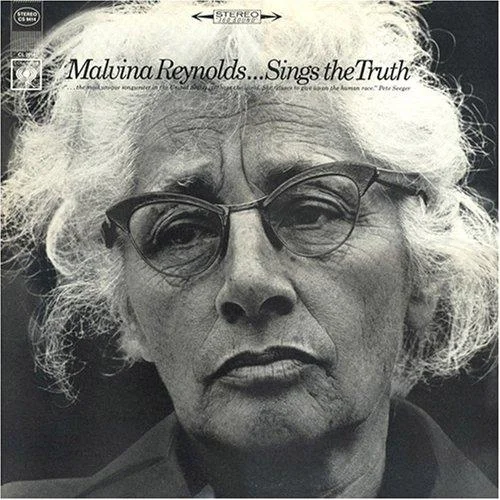

The album’s powerful black and white cover photograph was taken by the prolific Jim Marshall at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. The lines upon her face, and her at once serious and sympathetic expression, bespeaks a hard-fighting life, already well-lived. The coat she wore that day, which was bright white, as we can see in other photos, was smartly subdued in the album cover version, helping her contrasting, cotton-candy wisps of white hair to stand out.

Reynolds throughout her career shook cages with her music, and used it like a plow to turn soil for seeds to grow, or like a saw to cut to the core. Always at the root of her sword-crossing with those she disagreed, though, with was a central tenet of love and care for a flawed world. She loved it like a fool, this world.

But if there’s one takeaway from Reynolds’ life and work, let it be that each person has great power to effect change. In the fifth track, “God Bless the Grass,” she paints truth as blades of grass: tender, easily bent, and yet able to burst forth through the cement that aims to keep it down. After a while the grass lifts up its head, “for the grass is living and the stone is dead.”

One of my favorite examples of this idea comes in Reynolds’ song “The Little Mouse,” which was written in 1976, just two years before her death, and released posthumously on the album Mama Lion. That summer, she’d noticed a report in the San Francisco Chronicle that told of a mouse, loose in the Central Clearing House of Buenos Aires, that had chewed up a computer cable, thus disabling check-clearing operations for both banks and the stock exchange within the city. Reynolds, in her late 70s, sang the following:

“Hooray for the little mouse / that fucked up the clearinghouse / and set the stock exchange in a spin / and made the bankers cry! / So much for the electronic brains that run the world of banks and airplanes. / And if one little mouse can set them all awry, / why not you and I?”

I’m Josh Rutner, and that’s your album of the week.