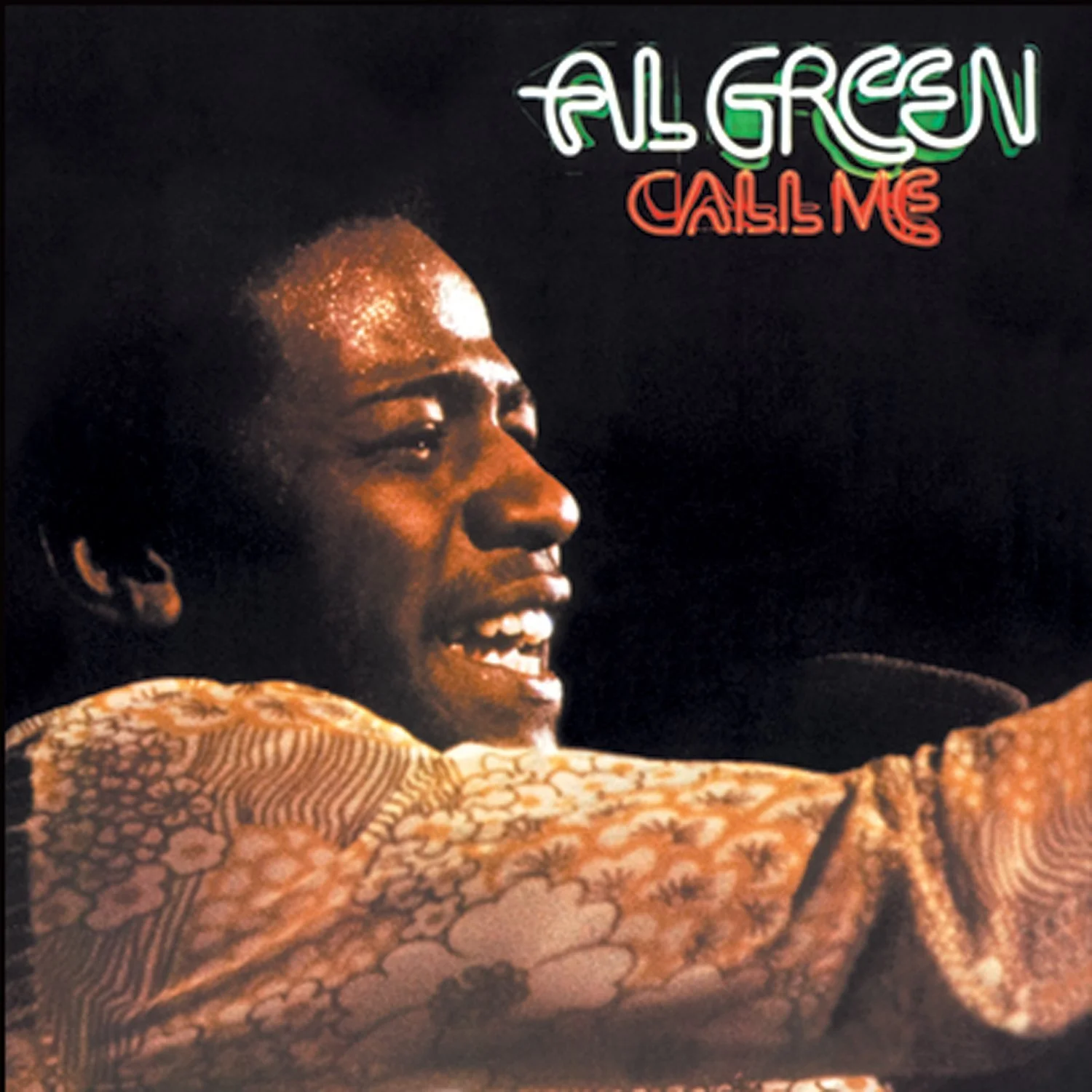

Episode 43: Call Me (Al Green, 1973)

Within his autobiography, called Take Me to the River, published in 2000, Al Green reminisced about one cold morning in a rural Michigan hotel room while on tour, approaching the window, which looked out “across the empty highway to the frozen fields on the other side”:

“As I watched while the sun slowly seeped into the dark sky, like milk being poured into a bowl, I felt myself standing in the middle of some great empty place, as if the universe and everything in it had been cleared away in a circle from all around me. It was a lonely, solitary sensation, but the strange thing was, I didn’t feel the ache of a man left to himself. It was more a peaceful feeling, a kind of soothing sensation, as if I was far away from every human sorrow and strife.”

Call Me, Green’s sixth album, released in the spring of 1973, was “supposed to be about nothing more than flirtation and romance and the hot passions that spring up between a man and a woman.” In truth, Call Me is much less about hot and heavy romance per se and more about the emptiness, the solitude, the loneliness of a pining lover.

Unlike “Let’s Stay Together,” his big hit from the year before, which is about an extant couple whom the narrator is lovingly suggesting stay together forever, the songs on this album circle around unrequited love, undone love, unbegun love. We hear a man who is crying out for lovers, sometimes nostalgically engaging with exes in stiff and stilted colloquialisms (as in “Have You Been Making Out O.K.,” and the cover of Willie Nelson’s song “Funny How Time Slips Away”) and sometimes pushing, pleading, praying (as in the title track and “You Ought to Be with Me”).

The following line from “Here I Am (Come and Take Me),” is indicative of the feelings expressed in this album: “It always ends up this way / Me begging you every day / A love that I cannot have / You broke my heart into half.” The love he can’t have in “Here I Am” is powerful, and even explosive—“All this love inside of me / I believe there’s going to be an explosion,” he sings—and therein, in that potential energy, lies the dramatic strength of these songs.

In Take Me to the River, Green wrote about what it took for him to shift—pressed by producer Willie Mitchell, with whom he had worked since their meeting in 1969—from his harder-edged, more “mannish,” Otis Redding-type vocal style into his signature floating falsetto, “like a little boy crying for his mama,” as Green put it, “or a grown man weak for the love of a woman. To sing like that,” he explains, “you’ve got to let something inside of you loose, give up your pride and power, and let that surrendering feeling well up inside until it overwhelms you and uses your voice to cry out with a need that can’t be filled.”

In a late-1970s interview with Lynn Norment of Ebony magazine, Green acknowledged that satisfaction is not his aim and even something he avoids: “I’m afraid to become satisfied, like being afraid to fall in love; it frightens me to death. When you are satisfied, you let yourself relax, and you don’t do your best.”

With this in mind, we might view the lack of fulfillment within the songs on Call Me as at least unconsciously self-inflicted—a sort of productive self-sabotage. The lyrics in “Here I Am” go on to say, “Keeping you and loving you means / Laying all my troubles down,” and when rubbed up against his statements above, we might conjecture that Green—the persona if not the person—is strategically unwilling to accept any such state of happiness, despite his entreaties for the addressee to “come and take me.”

In an earlier, 1976 article in Ebony, also penned by Ms. Norment, Green said of his millionaire lifestyle—his “money, jewelry, cars, houses”—that “none of that stuff means anything unless you are happy. I am not really happy.” After pausing, and staring out across the lake that his eight-bedroom Memphis ranch house overlooked, he continued, “What is happiness? To understand the reasons of life itself… things beyond my control. I have been in an arena with 40,000 people, but I was the loneliest man in there.”

Which brings us to another significant theme of Call Me: that of loneliness.

The fourth track, one of my favorites on the album, is Green’s cover of Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” The song was originally released by Williams 1949 as the flip-side to the danceable but lyrically lacking “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It.” “I’m So Lonesome” was never the hit that Williams knew it could be when he was alive, but it did eventually get its due. The start of the fourth verse alone—“The silence of a falling star / Lights up a purple sky”—is bursting with such bold poeticism as to make the tune a classic in my book. Lyrically, it’s not a narrative so much as a set of discrete metaphorical images of nature—falling stars, dying leaves, weeping robins, and so on—which is very much in line with Green’s outlook on the outdoors. He cites his earliest influences as “the rain on the window, the wind in the corn crop, or the water lapping on the banks of the river. That,” he says, “is music to my ears… I can still remember childhood days when I’d wake up early to the birds singing in the trees and throw open the window just to catch their whistles and chirps.”

He even tweaks Williams’ lyrics in the first verse, so strong is his love for such sounds, turning the lonesome whippoorwill who “sounds too blue to fly” into a lonesome whippoorwill who “sounds too good to fly.”

Loneliness is a complex thing.

Production-wise, this album is quintessential Willie Mitchell, with Green’s lighter-than-air velvet funk afloat high above the rhythm section’s nastily tight foundation. The horn arrangements are strong and the Memphis Strings are used effectively, and for the most part are not laid on too thickly or haphazardly. Green had, by this time—along with Stevie Wonder and others—joined Marvin Gaye’s multi-layered lead vocal trend, which Gaye had pioneered (at first quite by accident) on his 1971 album, What’s Going On. The hard-left panning and boosted levels of Green’s secondary lead voice can, admittedly, sneak up on you, particularly listening in headphones. He seems on this record to still be working out the kinks of the technique for himself, often providing I-just-sang-what-you-sang redundancies rather than complementary support.

That said, there are moments where that second voice shines, either musically, as in the harmonies on the choruses of the ultra-gentle, salivatiously close-mic’d “Have You Been Making Out O.K.,” or textually, as in the commentary on the lyric in “Funny How Time Slips Away,” in which “Never know when I’ll be back in town” is flat-footedly answered with an at-first seemingly innocuous, “maybe tomorrow.” Of course, the lyrics in the latter continue with, “Remember what I told you / That in time you’re gonna pay,” so, “maybe tomorrow” suddenly doesn’t feel as downright neighborly as it did a few seconds back.

In “Funny How Time Slips Away,” as the title suggests, time speeds by, such that so long ago seems like only yesterday; and, by contrast, in the other country cover, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” nights are so long, and “time goes crawling by.” Splitting the difference is the album’s centerpiece, “Your Love is Like the Morning Sun,” wherein the warm sun shining down is ultimately in the present of the narrator’s mind. As if bolstering this idea, the drums provide a reassuringly constant tick-tock cross-stick groove as Green—as ever the ex-lover—compares his love to a summer’s day. Her lease, too, it seems, had all too short a date: love faded to gray.

It’s enough to imagine Green alone, again, in a hotel room, facing the morning sun seeping into the dark sky, whispering to himself, “I'm tired of being alone / Still in love with you / Let's stay together, together.”

I’m Josh Rutner, and that’s your album of the week.