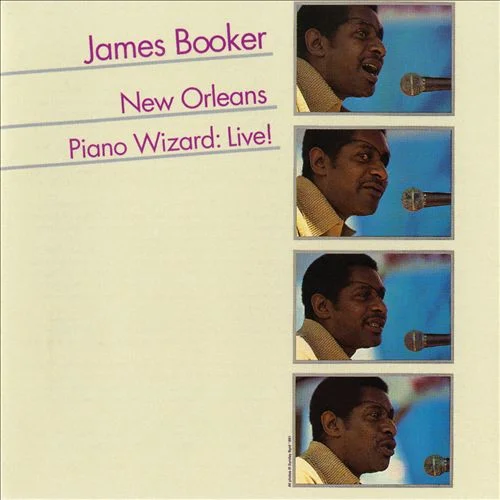

Episode 29: New Orleans Piano Wizard: Live! (James Booker, 1987)

In the 2013 documentary Bayou Maharajah: The Tragic Genius of James Booker—a film that only very recently was made available on streaming services—there is a full minute of footage containing people who knew pianist and singer James Booker telling the multifarious stories they had heard about how Booker had lost his left eye:

Goons hired by a disgruntled record contractor;

creditors who gave him a choice of an eye or a finger;

a fight in Angola;

the CIA;

a simple infection;

the Mafia;

a pool cue whack to the side of the head;

“something to do with Jackie Kennedy”;

defenestration;

plied out by an owed drug dealer.

Or, as a popular one goes, perhaps Beatle Ringo Starr put it out—sure, why not—and Booker memorialized the occasion by wearing an eyepatch decorated by a gold star. In the words of Booker’s old classmate Elaine Parker-Adams, “I’m sure Booker knew how he had insured himself. But you will never know.”

Booker was an enigma. A wild, unpredictable, hilarious, strung-out, don’t-give-no-bones-about-what-anyone-things, flamboyant enigma—who happened to be one of the most incredible pianists there ever was.

When producer Joe Boyd floated the idea that perhaps Booker record a solo album—just him and the piano—Booker scoffed, claiming if he was gonna make a record, he’d need his band. Three weeks later, as Boyd recalls, when Booker was in need of money, he’d gone back to Boyd and took him up on the idea after all—on the one condition, that is, that his piano in the studio be outfitted with a candelabra. Why? Why, he’s The Black Liberace, of course. Those studio recordings became the beautiful 1977 release, Junco Partner.

This album, titled New Orleans Piano Wizard: Live!—also just Booker and his piano—was recorded in front of an enthusiastic-if-rhythmically-challenged Zurich audience the same year as Junco Partner’s release, and posthumously re-released by Rounder Records a decade later, in 1987. From the first pair of tunes—the silver-lining-focused “Sunny Side of the Street” and the deep-and-dark blues, “Black Night” (a pair you could call Bookers’ theme songs, of sorts)—one is given some insight into the scope of Booker’s emotional range.

In “Black Night,” Booker sings with a birdless, existential loneliness what, in a lesser artist’s hands, might come off as a trite and cliched blues lyric: “Nobody cares about me / and I ain’t even got a friend / my baby’s gone away and left me / and when will my troubles end?”

On “Sunny Side of the Street,” rather than sing the usual final A section’s buoyant lyric as “If I never had a cent, I’d be rich as Rockefeller,” Booker ditches the analogy and simply, and powerfully, sings, “If I never ever had another cent, I still really wouldn’t be so worried.”

He had within his spidery hands many musical lineages from which he could draw. His parents were both pianists and they had outfitted him with piano lessons through age 12. In the few recordings he produced, you could hear Chopin in his harmonies; his alternately pillow-soft and knock-your-socks-off-with-one-punch touch bespoke years of diligent training. But of course the man was no conservatory conservative; he was steeped in music of New Orleans, and pulled too from the records of more well-known pianists. On New Orleans Piano Wizard, you can clearly hear the influence of Ray Charles on the patient, gospel-tinged slower blues numbers—particularly on “Come Rain or Come Shine”—and the steady left hand against the time-taking right of Erroll Garner on tracks like “Keep on Gwine.”

His chugg-a-lugging and modulating version of “Something Stupid”—which even nods for a few seconds in the direction of a cha-cha groove—is a tidy and sweet little gift that pushes the hungry audience to beg for more.

While “Something Stupid”’s lyrics, which, sadly, we don’t get to hear Booker sing, tell of the narrator going and spoiling a good thing by saying something stupid like “I love you,” I can imagine Booker playing it and thinking back to, say, when he and Dr. John, then involved with a bogus road act—passing themselves off as famous bands of the day like Huey Smith and the Clowns, whose “Rockin' Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu” had sold over a million copies—were pulled over by Mississippi state police after getting found-out and busted by a local promoter. While Dr. John envisioned the dungeon they’d surely be locked up in, Booker hopped from the car and told the cops, “Now look, don’t you worry ‘bout what the man told you. We threw the weed out the car miles back.” As Dr. John remembers, the cops laughed, they didn’t even search the car, and they just told them to get out of town and stay out.

Saying something stupid that went and saved the day.

To me, the crown jewel of the record is the penultimate track, the heartbreakingly raw love song “Let Them Talk,” a song that tells the whispering gossipers to shove it, sung by a man whose sexual predilections at the time surely elicited their share of talk. We hear here Booker standing most tall, open and defiant, as he lived.

If you’ve never heard James Booker, get into him with New Orleans Piano Wizard: Live!, and supplement that dose with the documentary Bayou Maharajah. They will open up your ears and eyes both. It’s likely Booker will never receive his full due. But ask any pianist in the know: many would give their left eye to play the way he did.

I’m Josh Rutner, and that’s your album of the week.