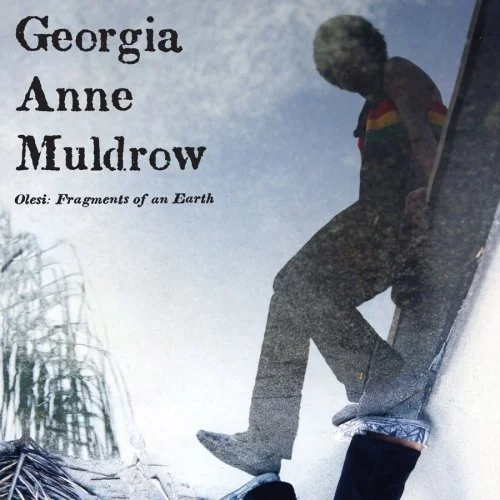

Episode 30: Olesi: Fragments of an Earth (Georgia Anne Muldrow, 2006)

In a 2013 lecture–interview for Red Bull Music Academy, Roots drummer and Tonight Show bandleader, Questlove, reminisced about his mid-'90s conscious unraveling of the metronomic precision he’d long strove for, sparked by producer Jay Dee’s work on The Pharcyde’s second record, Labcabincalifornia. The kick drum on one song in particular sounded, in Questlove’s words, like it was being played by a “drunk three-year-old.” In 1996, when recording D’Angelo’s epic album Voodoo, Questlove was pushed to the brink, recalling, “He constantly… wanted me to drag the beat but then he dragged the beat behind me.” Any of you familiar with Voodoo surely know the feel I’m referring to here.

For Georgia Anne Muldrow, that feeling of laying back—in a word, her swing—is innate and required no unlearning. If the backbone of the beat is the metronome, her music is the circulatory and nervous systems, lub-dubbing and firing on different planes but always in harmony. It’s as if she regards the beat as it goes by rather than riding atop it. In a dual interview with her mother, singer-songwriter Rickie Byars Beckwith, Muldrow admits with laughter: “I always clap late. My whole life—I clap late. I sing late, I nod late. I come to interviews late; I’m just—late!”

Her 2006 album, Olesi: Fragments of an Earth—her first full-length release—is a wonder of self-production, and, as the subtitle suggests, an otherworldly collection of snippets and snatches, some ending abruptly, some quickly fading out. 21 tracks under 50 minutes. For that very reason, this album is a great introduction to Muldrow’s work. The sampler-like record acts almost like a collection of journal entries—letting you in close for a peek, and then, the page turns.

The most substantial track—in length, if not subject matter—is the lead-off, called “New Orleans.” It is a brutally powerful opening statement, with Muldrow kicking the song off by singing, “Murderer / damage / a human life alone to die.” As listeners, we find ourselves awash in splashing cymbals, drowning in swirling ghostly background voices, and pounded and puctuated by an crooked machine-gun snare loop. Only one tiny window, at one and a half minutes in, offers a moment of relief—a brief chin above water, affording us just a half-breath—before being dragged again into the relentless deep. Muldrow’s voice doesn’t let up, approaching screams as she sings of the water and the flesh-and-blood it contains. Only in the last 15 seconds of the five-and-a-half minute song does the deluge recede, and she sings, “Listen child, dontcha know / It’s just my natural ebb and flow.”

In one interview, Muldrow tells of her formative memories hearing her father, guitarist Ronald Muldrow, playing "Giant Steps," which, for those unaware, is a composition by John Coltrane that was ground-breaking for its constantly shifting harmonic ground, never settling down into a “home base,” where complacency—in artist or listener—might creep in. That constant, clear-eyed vigilance and harmonic fluidity—the feeling of freedom to cross borders, or, better, eliminate them entirely—permeates Olesi. With squinting ears, one might even hear resonances of a beautifully wobbly cassette tape—the Doppler affecting the landscape.

Often compared to jazz luminaries like Nina Simone and Ella Fitzgerald, Muldrow once replied, in a manner that bespoke both her modesty and her bold ambitions, that, “for me, my aim is not to sound like Ella; my aim is to free my people.” Elsewhere, when asked about how she would hope people would see her legacy—what she’d want them to say about her—she took a beat, and said simply, “The greater legacy I hope to leave is what people will say about themselves.” For my money, Muldrow is less Simone and Fitzgerald, and more in the vein of June Tyson, the long-time vocalist with the Sun Ra Arkestra. I hear it in their sinewy melodic contours, their socially conscious and poetic lyrics, the space they don’t leave.

The indefinite article in the album’s subtitle, “Fragments of an Earth”; the name of her label, “Some Other Ship”; along with more overt references to outer space within Olesi’s lyrics, points to Muldrow’s hitching of her wagon to the rocketships of artists like Sun Ra himself, George Clinton, and others who used outer space references and iconography to explore such themes as alienation and identity in the Black experience.

Nearer to the end of the twentieth century, in a 1993 album, another vocalist and political activist, Abbey Lincoln—who, as it happens, like Muldrow also has a near-jarringly laid-backness to her style—poignantly invoked the outer reaches of the universe when she sang the following, in an ode to her mother: “Evalina Coffey made the journey here / Traveled in her spaceship from some other sphere / Landed in St. Louis, Chicago, and L.A. / A brilliant shining mother ship / From six hundred trillion miles away.”

Among the many tracks on Olesi, one can hear doo wop within boom bap, diamond basslines and parallel choirs, spoken word and rap and everything in between, salsa brass samples and garage beats, new-soul and old-school rubbing shoulders, and so on.

Olesi is a dense record, inhabited not only with Muldrow’s voice—or, rather, voices, what with her lush multi-tracking—but also the voices of generations before her. Her relationship to the past is deep and reciprocal: “I’m working on my receptive energy, for the ancestors to sing through me, so you’re going to hear a lot of different things because I’m giving them permission. And they’re giving me permission to sing, you see? And so I give them permission to use me to sing.”

On the track called “Wheels,” inspired by a John Outerbridge sculpture, Muldrow ties things up nicely: “Fabric of mankind is bursting at the seams / do as the birds do: keep singing ‘til you’re free.”

I’m Josh Rutner, and that’s your album of the week.